Easter Sunday, April 20, 2025 - Luke 24:1-12

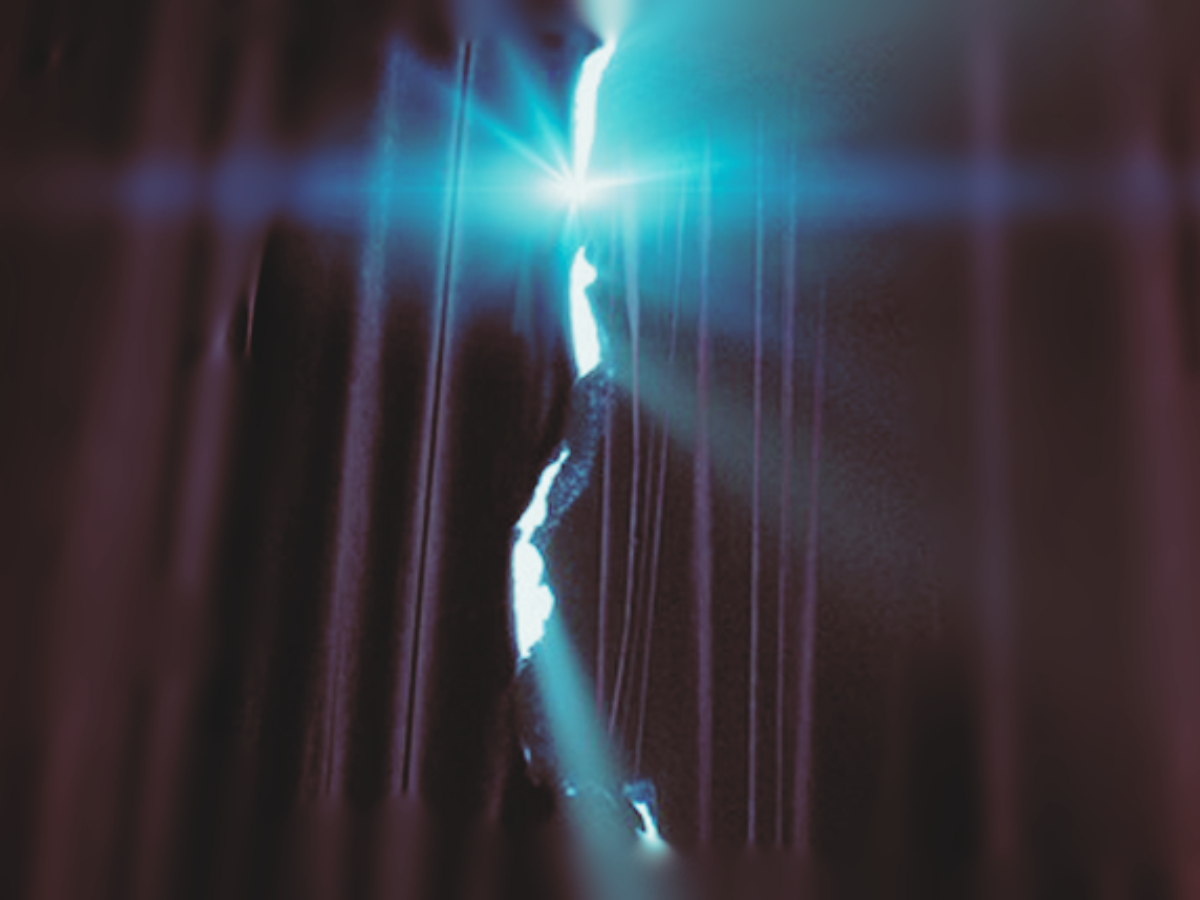

Tearing the Veil

Sunday, March 24, 2024 – Mark 15:1-39 [40-47] Also Isaiah 50:4-9a, Psalm 31:9-16, Phillipians 2:5-11, Processional Gospel, John 12:12-16

In the great archetypal stories of myth, fairy tale, and sacred texts, we see represented the deepest truths about the human condition that can only be told symbolically because of the limits of human language and comprehension. In fact, one of the saddest aspects of modern life is that we’ve completely missed the point about the language of myth, when we see the great stories as only about something that never factually happened when they’re actually about something that happens over and over again in human life.

Boundaries and Veils

An element common in myth is the boundary or veil between where we are now and where we need to be. Greg Lanier, an associate professor of New Testament at Reformed Theological Seminary in Orlando, writes about this, saying: “In The Lord of the Rings, the Doors of Durin bar entrance into Moria under the Misty Mountains. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, a mysterious wardrobe grants or prevents entrance into Narnia. And in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, a three-headed giant dog named Fluffy blocks entry to the underground chambers.”

We’re told of a similar boundary for the people of Israel – the curtain that blocks the entrance into the Holy of Holies where the Ark of the Covenant was historically kept. The Ark of the Covenant held the tablets of the law and marked the presence of God. It was described as a wooden chest coated in pure gold and topped off by an elaborate lid, known as the “mercy seat.”

At the time of Jesus, God’s most immediate presence was understood to be in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple. The people were never allowed into this holy space – even the high priest could only enter once a year at Yom Kippur. That’s when he would make special animal sacrifices to God to purify the people for the upcoming year and renew the covenant. The curtain that blocked the Holy of Holies was thick and didn’t let in any light.

You might remember a few weeks ago when I talked about how the people were so terrified by their direct encounter with the Living God on Mt. Sinai that they asked Moses to be their go-between from then on. They wanted those barriers of separation between them and God. According to Greg Lanier, the temple curtain “perpetually guarded the entrance to the holiest holy place.” But he points out that there are two significant exceptions to this reality in the Christian bible.

First,” he writes, “in a stunning vision of the future, the book of Revelation describes how, when Christ’s eternal kingdom comes, the heavenly temple will stand open (Rev. 11:15). The ark of the covenant—God’s throne in the Most Holy Place before being lost after the Babylonian conquest of 586 BC—will be seen by all (Rev. 11:19). No curtain blocks the way. But there is also a foretaste of this climactic scene on the day of Jesus’s crucifixion.”

In today’s gospel, Mark tells us that after Jesus dies, “the curtain of the temple was torn in two.” Matthew adds more detail, saying not only that the curtain was torn “from top to bottom,” but also that “the earth shook, and the rocks were split.” When Mark and Matthew say the curtain “was torn” they are both indicating that a divine energy is responsible. In other words, God tears the curtain keeping us from God’s presence. God doesn’t want to be separated from us.

While this reference to the curtain being torn in two is but one sentence in our gospel, it accomplishes so much in the story of the work of Christ and our relationship with God. I want to talk about four aspects of what that tearing accomplishes.

- Condemns the entire temple system

- Opens new access to God

- Establishes our anchor in the realm of the Spirit

- Marks the transformation from identity in human doing to identity in God’s being

Condemning the Temple System

In his blog, Lanier points out that “the tearing of this all-important curtain is part of a sequence signaling that the Jerusalem temple was losing its place as the heart of worship.” He shows how Jesus’ claim that he would destroy the temple, and his calling it forsaken and a “den of robbers” not only foretold of the second temple’s destruction in 70AD but also basically repeats the earlier condemnation of the first temple. He writes that the bankrupt practices the prophets condemned

led to God’s glory being escorted out of the temple by the cherubim, upon the temple’s destruction by Babylon (Ezek. 11:22–23). Likewise, the tearing of the curtain, apparently embroidered with cherubim, signified that Israel’s temple had again grown stagnant and would be undone.”

Once again, we see that elaborate rituals and practices in the absence of mercy and love are meaningless to God. God isn’t impressed by empty religiosity. The symbol of this entire edifice literally comes apart at the seams when the curtain is torn from top to bottom.

Opening New Access to God

Another point that Lanier makes is how before the curtain is torn, access to God is controlled by Temple structures of separation that keep women and gentiles in outer courts, far away from the holy presence, with Jewish men in the middle and the priesthood in inner courts with supposed direct access. This is the infrastructure of the first covenant where certain people are given special access. But now things are different. Lanier writes,

The overturning of the old-covenant infrastructure prepares for a new era. The torn curtain reveals that all believers have fresh, unparalleled access to God…The outer court of Gentiles was nullified by Jesus’s drawing all nations by faith. The court of women was nullified by Jesus’s making male, female, Jew, and Greek equal heirs of God (Gal. 3:28). And the priestly courts were nullified by his consecrating all Christians as a holy priesthood (1 Pet. 2:9). Throughout his ministry, Jesus demolished barriers symbolized in the temple apparatus. The inner curtain was simply the last.”

As we see in Paul, nothing can separate us from the love of God.

Establishing our Anchor in the Realm of Spirit

Lanier also links the curtain-tearing referenced in the gospels to the curtain mentioned in the letter to the Hebrews, and suggests that its tearing represents the entry of Christ into the heavenly holy of holies through the sacrifice of his bodily life. Through his sacrifice, Jesus penetrates the “inner place behind the curtain,” opening a “new and living way” through the curtain into the heavenly holy places. “The earthly veil is torn; the heavenly veil is opened.”

You see the symbolism here? The earthly curtain in the Temple was the physical boundary blocking the entrance to the earthly holy of holies. The tearing of that earthly curtain is mirrored in Jesus’ penetration of the heavenly or spiritual curtain that the was the boundary or gate at the entrance to the heavenly holy of holies.

In the letter to the Hebrews, we read that “We have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul, a hope that enters the inner shrine behind the curtain, where Jesus, a forerunner on our behalf, has entered, having become a high priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.” (6:19-20)

In other words, Jesus has gone ahead of us through the curtain and set an anchor there in the realm of God’s Spirit that links us irrevocably to our own ultimate destination.

Transforming into God’s Being

Finally, the tearing of the curtain shows the Christ event as one that transforms reality completely, moving us from an identity based in the law and human doing to an identity based in whose we are and in God’s being.

As Jesus entered Jerusalem, the people shouted “Hosanna!” which initially meant “please, save us!” The tearing of the veil opens us to the healing and saving grace of God’s life.

Whether we understand the tearing of the curtain historically or symbolically, it shows a key turning point in our relationship with God. And because the tearing of the curtain, at least in Matthew, is accompanied by an earthquake and the splitting of rocks, we see that both the natural and human-made worlds reflect this new reality. What we see is that the old covenant has now symbolically given way to the new covenant, the one where God’s law is written on our hearts. This is the new heaven and the new earth, where every single one of us is a child of God.

[…] We have now come to think of that word, “hosanna,” as a cry of praise, but as I mentioned on Sunday, it’s original meaning was “Pray, save […]